Food Producers of the Dordogne Valley

The main focus of last months trip to the Dordogne Valley was food, so for one of my final posts from the region I thought I’d put the spotlight on five of the hyper local food producers we visited who make the most of the ingredients so celebrated in the Dordogne Valley and Perigord regions: a truffle farm who make their own truffle oil and other truffle products, the famous Denoix Distillery in Brive, renowned for their walnut liquor, other spirits and violette Brive mustard, a goat farm where they make just some of the AOC protected Rocomadour cheese, a walnut oil factory, and a Bergerac vineyard and winery producing just some of the wines that served as the accompaniment to practically every single meal in the region.

Truffle Hunting at La Ferme de la Truffe

While I love eating truffles, it turns out that before I visited La Ferme de la Truffe to learn all about how truffles (particularly local Perigod truffles) are cultivated and harvested, I knew next to nothing. Now, a big disclaimer at this point: truffle season runs from November to February, so we were visiting the farm off season. Truffles were buried for more of a demonstration for how they were harvested while we looked around the truffle trees, but to be perfectly honest while I think the experience lacked the excitement of finding freshly harvested truffles, it still gave us a good idea of what goes on.

First, let us talk about how truffles get to be in the ground. While truffles to occur growing in the roots of trees in the wild (they’re like spores who live in harmony with the trees), truffle farmers buy special saplings where truffle spores have been introduced into the roots. It depends on the type of truffle and the type of tree, but in the wild it can take around 10 years for truffles to cultivate, but on cultivated trees it can only take about 5 years for for a tree to cultivate truffles. Truffle trees only really produce truffles for about 30 years, so this really starts to give a bit more background as to why truffles are so expensive!

A good indicator to tell if there are truffles forming in the roots of the tree is to look for a witches circle. You see how in the pictures there is a bare patch of soil around the roots of each tree where no grass has been able to grow? As the truffles form and live together in harmony with the roots of the tree, it releases spores that kill off everything else growing there. A useful tip for truffle hunting in the wild.

In the Perigod region, they use three different methods to hunt for truffles: the pig (a little old fashioned, and something they only really do for tour groups etc. now), trained truffle dogs, and flies. While most people know about training pigs and dogs for hunting for truffles, I had no idea that if you’ve got a keen eye, you can find truffles by spotting a breed of local fly that hovers around the ground above a truffle as they can detect the aroma.

Truffle hunting was demonstrate for us by a pair of trained truffle dogs. They train them using small pieces of truffle and the aroma from truffle oil, and once they’ve unearthed a truffle from the ground they’re awarded with a piece of cheese. This is part of the reason they no longer use truffle pigs much anymore; while the dogs are more than happy with their cheese, you needed to keep an eye on the pigs as sometimes they were more interested in snaffling the truffle they’d unearthed themselves!

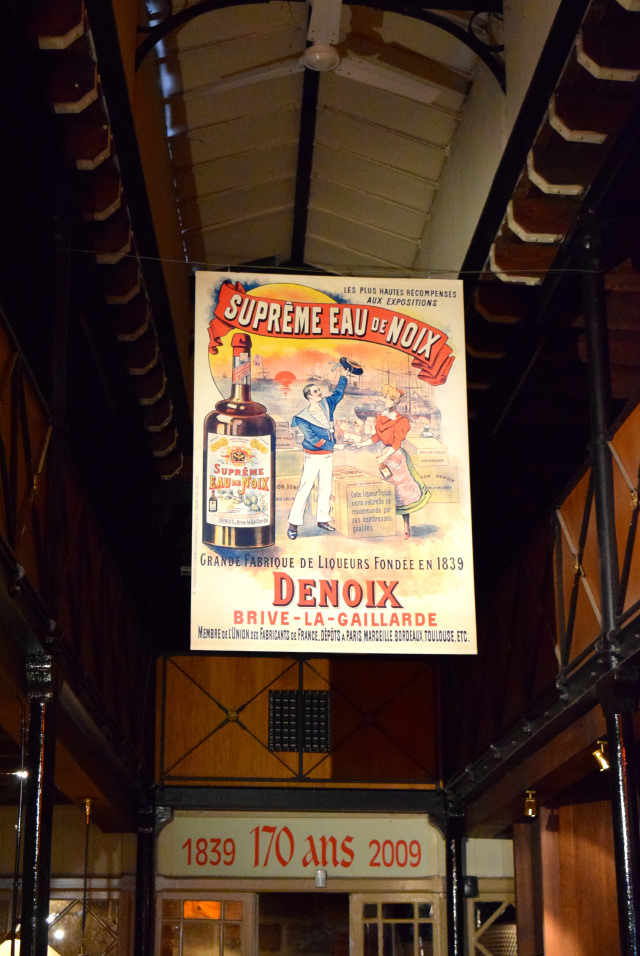

La Suprême Denoix Liquor and Moutarde Viollette de Brive at Denoix Distillery

While it is not particularly known outside of France, inside the country La Supreme Denoix is a very popular walnut liqueur perfect for an aperitif (mixed with something light), digestif (by itself), or as part of a cocktail. It has been made at the Denoix Distillery by the same family for generations in Brive, and it is worth a trip to the distillery for a trip to their archive, for a nosey around the distillery where they still use traditional equipment and method, and to pick up a few bottles of this unique, slightly chocolatley nut liqueur.

While the main attraction at Denoix is their famous walnut spirit, they also produce a whole myriad of naturally derived liquors from everything from fennel (with a strong aniseed flavour) to cocoa nibs (which curiously tastes less like chocolate than the classic walnut version!) Here we’re being shown how (the frankly incredible smelling) orange peel curaçao being seeped in alcohol before being blended with a sugar syrup. You know that blue stuff people put in tropical cocktails? This is that, but a more natural version!

Another family recipe worth picking up at the distillery is their 1839 recipe (the family used to be that the men handled the booze and the women made the mustard) for Brive’s typical Moutarde Violette, a purple mustard coloured and flavoured with grape must. You can get versions all around the area, but this was my favourite out of the jars I sampled. Think of a slightly rounder French mustard with a sweet underlying sharpness. I put a jar of it out with homemade sausage rolls as guests arrived before we sat down to eat on the Bank Holiday, and slightly irritatingly everyone was more enamored by the mustard than my sausage rolls!

Rocomadour Goats Cheese at La Borie d’Imbert

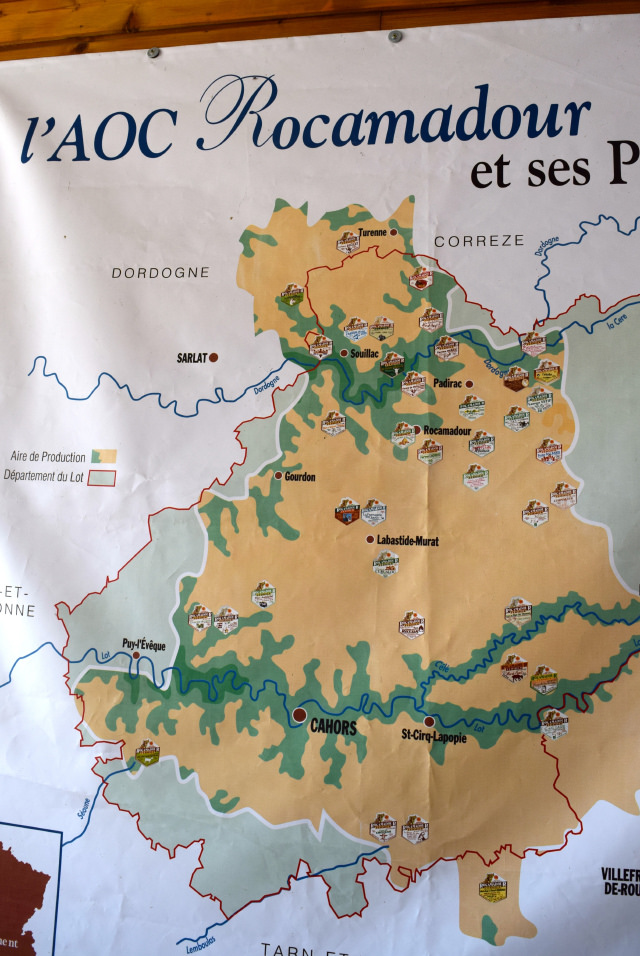

Aside from the famous pilgrimage site, the thing the Rocomadour area of the Dordogne Valley is famous for is its little soft rounds of Rocomadour Goats Cheese. I don’t often write about cheese here because I can’t eat most of it, but because I’m all good with goats milk I was very excited to visit one of the many goat farms (one of 39 in fact) who are allowed to make Rocomadour goats cheese as part of Rocomadour’s AOC designation.

The cheese is shaped from raw, unpasteurised goats milk and left to dry out on wire racks which is what gives its thick crust (preserving the soft, slightly gooey centre, making the cheese fantastic for baking) Rocomadour’s characteristic lines. Typically it is left to age for 12-15 days, but some of the greener (okay, mouldier) cheeses you can see here have been left for ages; the cheese actually comes in a spectrum, where in the Lot everything from the usual soft and mild to very hard and strong cheeses are produced.

Walnut Oil at Moulin a Huile Castagne

Have you ever stopped to think exactly how walnut oil is made? While walnut trees can grow anywhere (case in point, we have one in our front garden in Brittany), the Dordogne Valley are mad for their walnuts. On so many stops, especially around the Brive area as gifts we were presented with bags of candied walnut halves, and I was head over heels for the walnut bread at Chateau de la Treyne. Our trip to the Moulin a Huile Castagne (where they’ve been pressing oil for three generations, and where they have a nifty, walnut product restaurant upstairs) really made me at least respect how my oil is made a hell of a lot more. I say respect because there are so many things we pick up cheap off of the grocery shelf every day to use in our cooking without actually thinking of the care and craftsmanship that goes into it.

First, walnuts are shelled and crushed into a rough paste. That paste is then roasted over a fire (fuelled by the walnut shells that would have otherwise been discarded), being turned occasionally. It is here at the roasting stage the strength of the oil and the flavour can be regulated; through experince, the oil maker knows just how much roasting and toasting the nut pulp needs to make everything from a mild to a strong flavoured oil.

The pulp is then shovelled into the press to create two products, freshly pressed oil and these disks of dry compacted walnut pulp which can be used as animal feed. The whole process is rather mesmerising to watch, and the smell that comes from the crushing, roasting and pressing of the nuts is simply divine.

Bergerac Wine at Chateau de Panisseau

You cannot talk about the Dordogne Valley without talking about the regions wines. Almost every single bottle that was opened for us on the trip was from within at least the department, if not just a few miles away. The local wines have a sweetness, while still being perfectly drinkable to pair with everything that we became overly familiar with throughout the trip, and once we arrived in Bergerac the fields out of the car window turned into mile upon mile of vines and wineries as far as the eye can see.

We spent our last night of the trip in the gites at Chateau de Panisseau (the chateau itself is still under renovations, but will be available to rent out and stay in too when it is ready), clustered around the courtyard across from the winery, in the midst of their vines. They speak English, so it is a great place to get to know the wine of the region, and for perhaps a quieter week in the middle of a vineyard (it is so wonderfully quiet and out of the way), enjoying the wine, swimming in the pool and relaxing in the French sunshine.

I’ve explained the rudimentary steps of wine making in this post from La Rioja in Spain, but I learnt a few more tidbits about wine making both in the region and in general exploring their winery. As part of their AOC (the French designation for a protected food region) Bergerac wines have to be blended. You’ll never get a single grape Bergerac. Speaking of blending, did you know that blending experts are almost always not from their own vineyard? They believe that getting an outsider in helps the vineyard get an impartial view on their wines.

Finally, you see those round wine storage vats built into the walls? They used to be all they used, bare concrete walls and all. For obvious food health reasons the EU banned their use, so lots of wineries who could not afford new technology had to close. However, a few at Chateau de Panisseau are still in use; after cleaning them out (a whole person can climb in to pressure wash!) they had them coated in a form of rubber to make them sterile. it is very expensive to do, though!

It was absolutely pouring with rain the day when we woke up in the vineyard, so we decided to forgo a bicycle ride through the vines in favour of (a 10am!) wine tasting. Here you can see the new branding of wines from the vineyard (the rose was my favourite, so pale it is practically clear in the glass). However, I was head over heels with their vintage wine, though then again I’m a sucker for wines that have had a chance to mature.

If you know anything about French food you’ll know that it is fiercely regional, so I hope I’ve managed to give you a little taste of just some of the flavours of the Dordogne Valley and the Perigod here, giving you both an idea about their production, and simply just an idea of what to look out for when you’re planning a visit.

I was a guest in the Dordogne Valley of Brive and Bergerac Airports and the local tourism boards. Thank you La Ferme de la Truffe, Denoix Distillery, La Borie d’Imbert, Moulin a Huile Castagne and Chateau de Pannisseau for their hospitality.

Discussion